Solving a 1906 Mystery - Is Elizabeth Pass misplaced on maps?

For those interested, here is a list of my gear that I have found works well for me. This is, of course, an affiliate link and your enjoyment of these may vary:

You're going to laugh. I am up to my sleuthing again.

Recently I posted a lengthy blog post on recreating my 1987 trip to the Tunemah Trail based on photographs and sketchy evidence. Using Google Earth and other maps, I was able to piece together and solve the mystery of that trip.

In *this* blog post, I solved a new mystery and figured out that Elizabeth Pass in the Sierra Nevada is mislabeled on topographical maps. Not that anyone else cares, but for me, this was a fun find. I promise this is a lot shorter than my last research post. It's still long, though.

The Setup

This time, I was browsing my old photos for a Throwback Thursday #tbt Instagram post when I came across the photo above. I had assumed this was from one of my several weekend trips with the scouts back in the 1980's. We typically went to the Southern California mountain ranges, like San Jacinto or the San Bernardino Mountains. I wanted to figure out where this was when I noticed the sign. I zoomed in on the photo and read the inscription.

I had no recollection of this.

From the picture, I had the following information:

It was on a Boy Scout backpacking trip in the 1980's

At least 5 tents are in the photo, one was George's, a father of one of my troop-mates, the rest were our troop's tents

Approximately 10 people were on this trip

It was located at a place called Stewart Edward White Camp

It was somewhere near a pass

I googled "Stewart Edward White Camp" with and without quotation marks. Surprisingly, nothing came up that matched what I was looking for. I then researched who White was and found out he was a prolific author back in the early 1900's, writing adventure books mainly about the outdoors. After more research, I realized that he wrote a book called The Pass, published in 1906. Since his books are in the public domain in the US, I was able to find a free copy online and started reading.

It read a little like a blog post of a trip report. I skimmed the content looking for location information. The first paragraph mentions Big Meadow Trail, which I was sure wouldn't be very helpful. I was focusing on Southern California and not getting any hits. I found Big Meadows all over the place, from the Lake Tahoe Basin to the Domelands area in the Southern Sierra, but I hadn't been to any of them, except the one near the Tunemah Trail. But we hadn't had that many people on that trip. I had also camped at Big Wet Meadow in 1984 on my Sierra Trip to Mount Whitney, but I didn't think that was it. So I continued to read.

He described Big Meadow in detail, but it could be anywhere, typical of any high Sierra meadow. In the book, White gets a tip from a ranger at Big Meadow that there is truly beautiful and remote country up near Roaring River.

"Somehow the names fascinated me - Roaring River, forking into Cloudy and Deadman's Cañons, beneath Table and Milestone Mountains in the Great Western Divide. It is a region practically unvisited." - The Pass, 1904

These were places I could find and found them easily. I decided to follow his explorations on topo and google earth maps starting at the Rowell Meadow Trail through Sugarloaf Valley and into the Roaring River drainage, to see if I could get a sense of where the camp in the picture was.

It was at this point that I started to realize that the picture was likely taken on my 1984 Sierra Trip to Mount Whitney, since we had traveled through Cloudy Canyon to get to Colby Pass. In fact, I had seen Deadman's Canyon from our trip, as I discovered below, by researching Google Earth and Panoramio.

Deadman's Canyon from Moraine Ridge 1984

So I researched the places where we had camped on our trip:

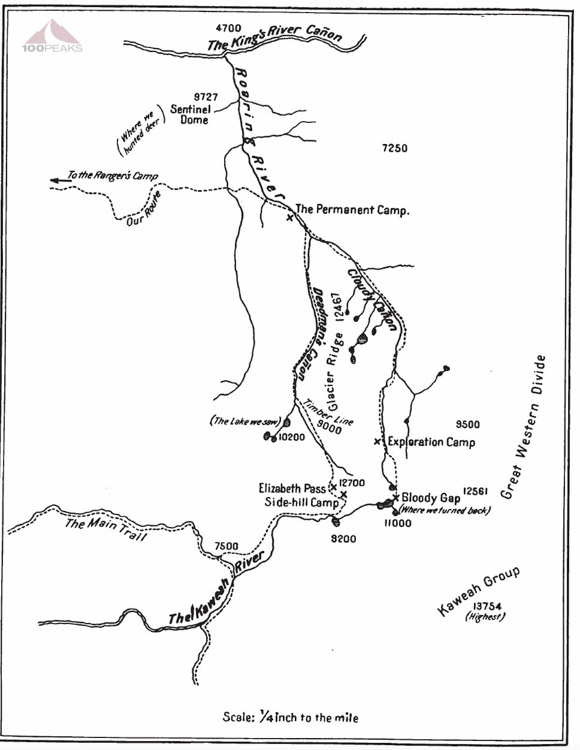

The picture below was from the book:

This is the picture that made me pause. I scoured Google Earth all the way down what is now labeled Elizabeth Pass and could not find where the photo above was taken.

These next two photos are what made me think I was onto something:

I had come across some proof that the way they descended, and the Elizabeth Pass they mentioned, was different than what is labeled on our topo maps. This green ledge was over Tamarack Lake, nowhere near the Elizabeth Pass labeled on USGS maps.

I went back and reread the sections about their attempts to find a pass over the Kings-Kaweah Divide.

Attempt #1

On their first attempt, they rode to the end of Deadman's Canyon where, "There, to my delight, I discovered an old miner's trail leading leftward of the falls through the greenery, which turned out to be tall brush." Before long, he reaches an old miner's camp and then reaches the end of the snow, and writes one of my favorite passages:

"It forced home a feeling of the discrepancy between what a man can conceive and what he can do. Here I can leap by one eyesight to the valley of Tuolumne, yet it would take me about three toilsome weeks to make the notion good."The Pass, 1906

He gets to Coppermine Peak and decides that the lower pass he sees to the east, at the head of Cloudy Canyon is going to be the way to go.

Note exhibits A and B below which tell the story of this attempt:

"In the process, he [Wes] reported an interesting view and a fine glacier lake." Wes had explored to the west and apparently found Big Bird Lake:

Attempt #2

They headed back to where Deadman's and Cloudy Canyons met and headed up Cloudy Canyon, sure that they would find a way over the divide and down into the valley. They went up the east side of the canyon, past Glacier Lake and up and over what they called Bloody Pass, which is now called Triple Divide Pass. They were sure that the way down to the valley would be easy once they got there. They were wrong. They got stopped by a cliff before the large glacial lake below. They nearly killed their horses and themselves in the process, just having to reverse the way they came and camp a cold and rainy night in the higher reaches of Cloudy Canyon before they returned to Scaffold Meadows, making a pleasant permanent camp for about 10 days.

The irony of their disappointment is that even if they had made it to that larger lower lake, they would have been in for a surprise of a 1,200' drop into the Kern-Kaweah Canyon. After their night out, White sends the others back to Scaffold Meadows, while he decides to go back to near where he went during attempt #1 and start forming a trail down.

""I will climb the ridge again," said I, "and look for a route over from the other canon [Deadman's Canyon]. You can make camp at the meadow where the two canons come together [Scaffold Meadow], and I will join you about dark."

Attempt #3

Having gone back up to Coppermine Peak, he looks for a way down:

He prepares a trail to the trees and figures they'll figure out a way down once they get there. He heads back to Scaffold Meadows and camps. The next morning, the whole team goes back up Deadman's Canyon, "The old trail to the prospect holes part way up the mountains we found steep and difficult, but not dangerous." They reshod a horse on the trail and "Thanks to my careful scouting of ten days before, we had no trouble at all in reaching the "saddle.""

They were happy to have reached the top and, in a pivotal moment of celebration, christened this pass, Elizabeth Pass.

"In the meantime, however, having finished our hardtack and raisins, we poured about two spoonfuls of whiskey over a cupful of snow, and solemnly christened this place Elizabeth Pass, after Billy. [...]It proved to be a little over twelve thousand feet in elevation."

It's interesting to note that the pass that I propose to be the 'real' Elizabeth Pass is about 12,275', and the one labeled on the USGS maps is about 11,375'. Another notable section:

"We cached a screw-top can in the monument. It contained a brief statement of names and dates, named the pass, and claimed for Billy the honor of being the first woman to traverse it."

They made it down to the trees and made a "Side Hill Camp" as is the title of the next chapter. From there, they went down the green ledges in the photos below:

Having passed the hardest part, they made it down to the lake and ultimately down to the valley and found the trail.

The Question: Why is Elizabeth Pass misplaced on the USGS maps?

My possible answer has to do with the fidelity of the old maps and the establishment of an easier trail in later years to the west.

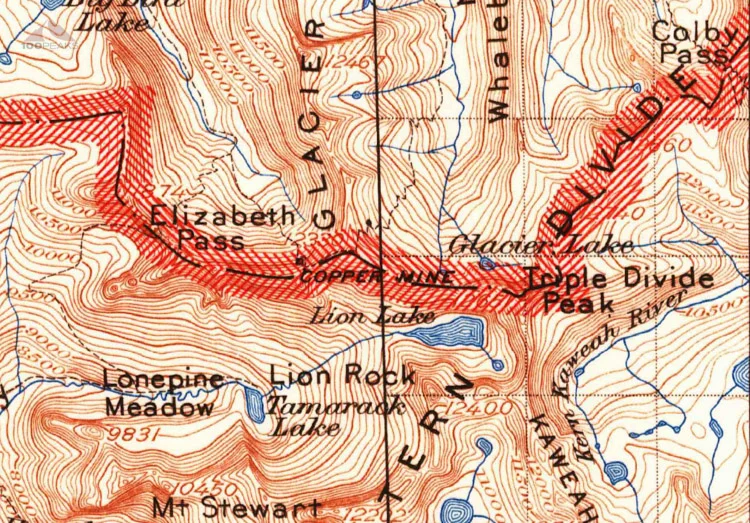

Here are a series of USGS Topographical maps from 1903 to 1988:

This 1903 version shows Elizabeth Pass in a large font, and it's hard to be sure where it is, but there is a gap in the border right where the pass could be by the copper mine. However, it's likely placed too far to the west already.

This 1905 map above actually shows the trail that White drew at the back of his book (see below). It erroneously goes straight up to the divide, rather than angling to the mine, as shown on White's map below. The label for Elizabeth Pass has been moved to the west, possibly to reference the portion of the newly added trail that crosses the divide. Later mapmakers will assume it is to reference the easier trail that passes underneath it.

The 1956 and 1988 maps show Elizabeth Pass where we now know it.

Update: 09/15/2015

I forgot to add his trail notes from the back of the book, which is very telling. And I found a picture of the very area they descended.

Getting there:

Regular trail into Roaring River. Ascend west fork of river; proceed by monumented and blazed miner's trail to cirque at end of canyon. When a short distance below the large falls, at a brown, smooth rock in creek bed, turn sharp to left-hand trail.

Climb mountain by miner's trail to old mine camp. If snow is heavy above this point, work a way to large monument in gap. The east edge of snow is best.

The way down:

From gap follow monuments down first lateral red ridge to east. This ridge ends in a granite knob. The monuments lead at first on the west slope of the ridge, then down the backbone to within about two or three hundred yards of the granite knob.

Turn down east slope of ridge to the watercourse. Follow west side of watercourse to a good crossing, then down shale to grove of lodgepole pines. Cross west through trees to blaze in second grove to westward above lake. Follow monuments to slide rock on ledge. Best way across is to lash a log, as we did. Follow monuments to knoll west of first watercourse. Turn sharp to left down lateral ridge for about one hundred feet. Cross arroyo to west, and work down shale to round meadow.

From meadow proceed through clump of lodgepole pines to northwest. Keep well up on side hill, close under cliffs. Cross the rock apron in little canon above second meadow. Work down shale ridge to west side of the jump off below second meadow. At foot of jump off pass small round pond-hole. Strike directly toward stream, and follow monumented trail.

Update 09/16/2015

It has been brought to my attention that the book mentioned in this post, The Pass, was first published in 1906, not 1904 as I so confidently declared above. I also put the year in the name of this article. I have no idea where I got 1904, so I am going to make up a story like, perhaps Stewart, Billy and Wes made the trip detailed here in 1904 and the book wasn't published until two years later. That seems feasible, right?

Also, it turns out that the USGS knew of the misplacement and were OK with it, as it was named "near the present pass to which common consent has shifted the name."

US Forest Service Decision Card approved in 1928

Per Farquhar:

Stewart Edward White and Mrs. (Elizabeth Grant) White crossed from the head of Deadman Cañon in the Roaring River country to the Middle Fork of Kaweah River and named the pass for Mrs. White. (White: The Pass, 1906, pp. 157-158.) The account of their expedition was first published in Outing Magazine, March, April, May, 1906. By mistake, they crossed the divide a difficult route. The name is now generally accepted for the true pass, a little to the west of the one used by the Whites.

Conclusion

What now? I guess I feel satisfied that I made a case that Elizabeth Pass has been misplaced on USGS maps. And that's about it. That and I identified where the photo at the top of the post was taken.

I doubt the USGS will change the location of the pass, since there are likely a lot of references to this pass in a lot of maps and guidebooks. There's an official process with the USGS, but I doubt I will even try. [It turns out they knew it all along. I didn't really discover anything. See 09/16/2015 update above. But it was still an exciting riddle to solve.]

The exercise was fun in itself. As it should be.

Also, perhaps I now have another Sierra Nevada backpacking itinerary, ready to go, when I am ready.

And Craig, I hope you like this one, too.